ISSUE 96, FOOD OF THE 50 STATES, Part 5: Missouri

Missouri

If there is one state in the United States I wonder about most in terms of its local foods, it would be Missouri. When you see a listing on the internet of the signature foods of Missouri, you see concoctions of dating from the mid-20th century and later: gooey butter cake, burnt ends, pork steak, toasted ravioli, the St. Paul Sandwich. All were creations of city eateries and little reflect the extraordinarily rich agriculture and country foodways of the state since its settlement. The native corn, squash, beans, and plums of the Kaw, Quapaw, and Missouria Peoples were a bounty that French, German, and Anglo settlers embraced as they exerted dominion over the region.

The historians of Ste. Genevieve in Missouri have made a study of that town’s original cuisine. According to Bob Mueller, soup was the central dish of that cuisine, and chicken bouillon the favorite form of soup. The bouillon was simple: vegetables, a fat hen, salt, and water. {Germans would later add tomato juice into this soup in the mid-19th century] Early reporters also noted the prevalence of vegetable soups, gumbos, and fricassees. William C. Carr, a lawyer and no fan of French fare, wrote a critical letter in 1804, cited by Mueller: “The breakfast is composed of a single cup of coffee with some bread without butter; the dinner of soup, very seldom of any other kind of meat besides that of which the soup is made together with lettuce of which the French are extremely fond, using with it some kind of oil, commonly Bear’s oil.” [https://mofolkarts.missouri.edu/2017/12/24/bouillon-a-missouri-french-tradition-by-robert-mueller/]

When the Women’s Club of Ste. Genevieve published in 1959 Recipes of Old Ste. Genevieve, their research could uncover little of the French first phase of the community’s cookery. The earliest traditional recipe come from the second phase of settlement in the city, when Germans began dominating local culture in the mid-19th century—a formula for liver dumplings supplied by the Old Rock Building.

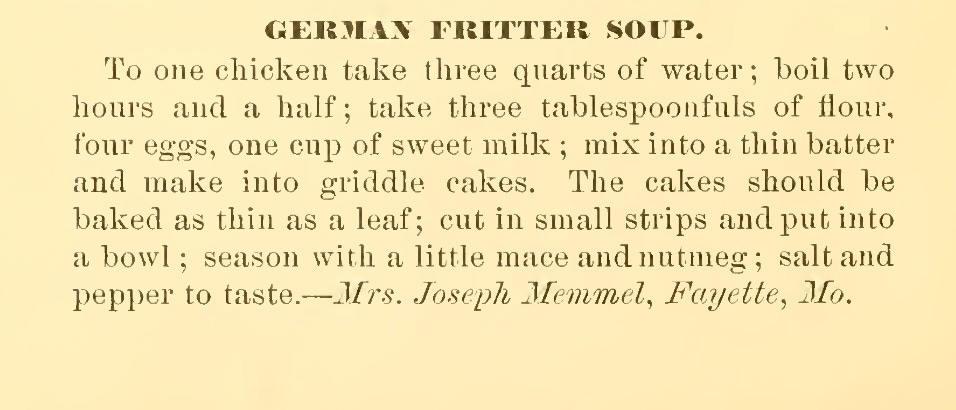

I have spoken about the refinement of German food culture in Missouri in my profiles of Faust’s Restaurant in St. Louis. But the German vernacular cookery in small towns and the countryside is best tracked in publications that come from places other than St. Louis and Kansas City. In 1887 the Ladies of the Baptist Church of Fayette, MO, published The Missouri Cookbook. While it contained the expected multitude of oyster recipes, cakes, and jellies, the collection captures numbers of the Missouri-German classic dishes, such as Fritter Soup, Vinegar Baked Ham, Veal Cutlets, Souse, and Rabbit Stew.

Other dimensions of German culture had as much influence as the repertoire of Old World dishes. Missouri became an important center of wine-making and pomology thanks to German vintners and orchardists. They were particularly innovative, realizing the Vitis vinefera grapes of Europe would succumb to the diseases rampant in American vineyards—black rot, mildew, Pearce’s disease, etc.—they embraced hybrids of native American vines and European. These varieties had American disease resistence and taste qualities similar to European grapes: Cynthiana, Catawba, and later Seyval and Chambourcin. Hermann, Augusta, and Rolla became centers of production and Missouri ranked second in volume of wine production of the United States on the eve of Prohibition in 1919.

Anglo-American cookery in Missouri begins with the hog and hominy of the Ozarks. This baseline southern style of food characterized Ozark food until the mid-twentieth century when Kansas City beef made inroads and supplanted work with roasts, steaks, and barbecue. While Kansas City made barbacue an ecumenical matter, treating chickens, pork, and beef, it was the beef ribs prepared by Arthur Bryant and Gates & Sons, low and slow, that made the city’s barbecue world famous. In contrast, St. Louis barbecued short ribs and grilled and sauced rather than being smoked and cooked low and slow.