ISSUE 8, CHARLESTON, Part 2: Mac & Cheese

Angelo Santi, did he introduce the South to Macaroni & Cheese in 1794?

Angelo Santi (1756-1817?)

Confectioner, distiller, merchant grocer, and tavern keeper Angelo Santi (1756-1817?) introduced Lowcountry residents to the splendor of Italian cuisine. He brought pasta to Charleston, selling shop made vermicelli and macaroni (the genesis of the region’s love of mac & cheese), imported Spanish chocolate and cocoa butter pioneering its use in confectionery (Charlestonians knew it exclusively as a beverage), cured his own meats and made pâté. A native of Bologna, Italy, Santi introduced the namesake bologna sausage to the South.

A widower, he came to Charleston with his son Joseph in 1794, at age 38. He carried with him an elaborate 4 piston crank street organ that could play 30 popular melodies, copper stills, and a thorough schooling in both French and Italian styles of confectionery. He attempted to raise money by raffling off the organ, but the raffle met with such little success that he was forced to sell at fire sale prices in Spring of 1795.

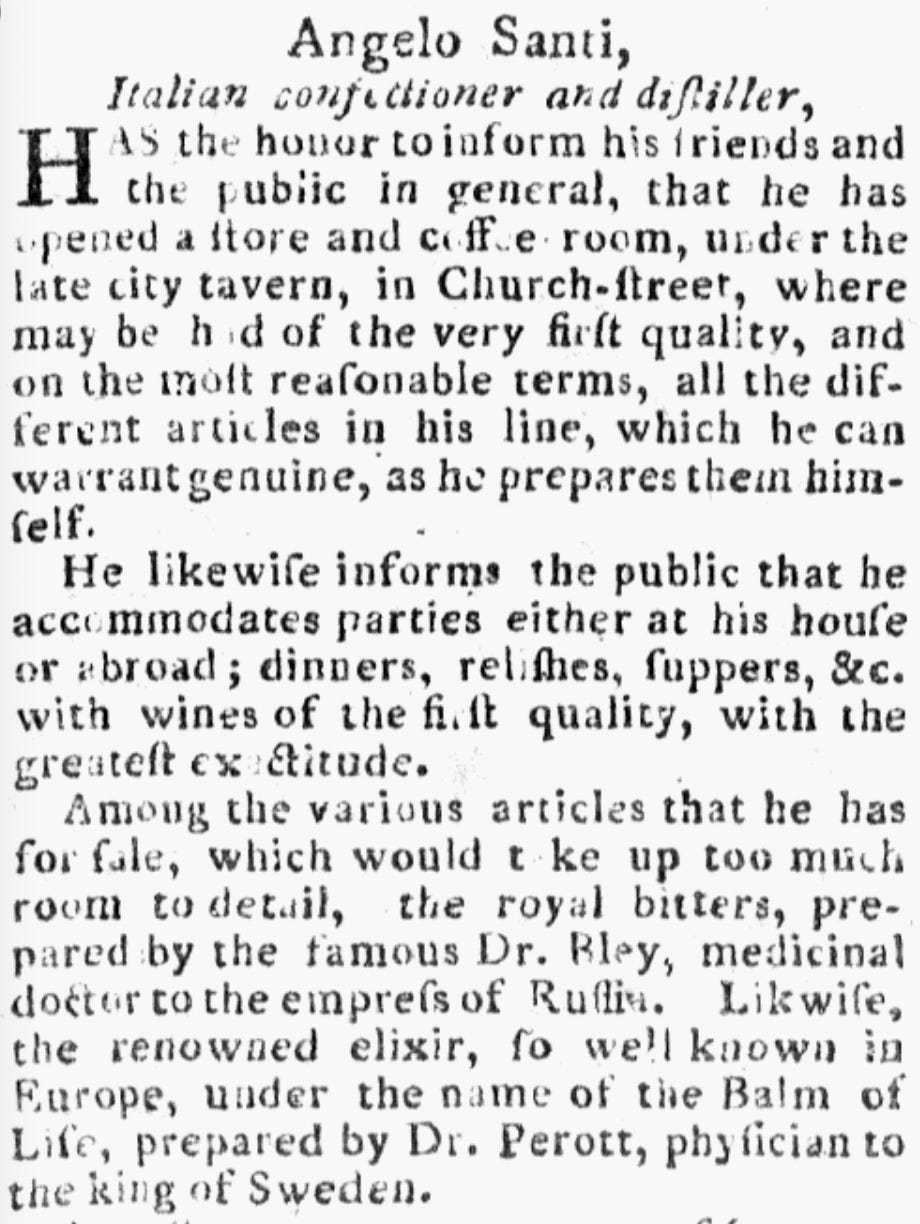

The connection between sugar and alcohol was something that professional confiseurs were trained to understand at the end of the 18th century. So it is not surprising to see him set up business as a “Confisieur et Distilateur Italien.” His initial advertisements in English and French announced his mastery of the production of spirits of every strength and quality, orgeat syrup and vinegar, cordials, and bitters—particularly the famous digestif produced by Dr. Bley, the English physician to the Czarina of Russia.

Santi secured the ground floor of the City Tavern at 86 Church Street, on the corner with Mulatto Alley. The Tavern’s public rooms were on the second and third floors. He announced a willingness to cater parties and dinners, supplying everything from relishes to wine. He discovered that his chief competition lay in confectioner Archibald Ponton on Tradd Street. Santi had an advantage over Ponton; the Italian could make candies and confections, and distill spirits and medicines; Ponton could only import his wares. By 1799 Santi had driven Ponton out of business.

What decided the contest in Santi’s favor were the cakes and hot tarts produced at Santi’s shop from noon onward. Indeed, after driving Ponton from the city, Santi decided to scale back the distillation and take up Ponton’s kind of import business, bringing spices, fruits, and alcohol from Europe into South Carolina. This required another sort of space—less a manufactory and more a store and dram shop. He found a premises at 60 King Street.

In March 1804 He married widow Francoise Judeh L’Etange Gilleron. Her two children came into the household. Meanwhile, Angelo’s son Joseph, moved to Savannah and set up a similar business there. The Santi family would increasingly project a presence in that city. Francoise Santi would die there in 1811 and her will would be executed in Chatham County, not Charleston. Shortly thereafter, 56 year old Angelo wed again, marrying Henriette Dupont, a Haitian expatriate, in Charleston n January of 1812.

Angelo Santi was a mobile soul, restlessly moving around Charleston, and back and forth between Charleston and Savannah. In 1807 the confectionary moved to 81 King Street, on the corner with Clifford. In 1808 he relocated to 20 Market Street. There he secured a billiard table and dispensed alcohol to quaffing patrons. In 1813 he moved to 41 Meeting Street. In 1816 when he turned 60 he visited London and decided to shift his base of operations to Savannah. The death of his son’s business partner, confectioner Charles Louis Payart in 1814, convinced him that more business was to be had in Georgia.

One reason for going to Savannah may have been the proximity to Ebenezer, Georgia, where the finest pasta wheat in the South was grown. The Salzburger religious community had settled there and established its famous mills in the 1750s. They secured timilia durum wheat from Sicily to grow and mill. Though the community had dispersed at the end of the 18th century, the wheat continued to be grown by farmers northwest of Savannah because of its quality.

Angelo Santi’s ability to conduct business in two cities and to refit his shop repeatedly no doubt derived from his five enslaved workers. One of these, James Custer, became an adept at confectionery and distilling. Another, named Samuel, whom he bought from Renee Godard, in 1803, he trained as a sugar baker.

Angelo Santi last appears on a Savannah tax register of 1816.

“Angelo Santi,” Charleston City Gazette (August 16, 1794), 3. “Rafle,” Charleston City Gazette (September 16, 1794), 4. “To Lovers of Music,” Charleston City Gazette (May 23, 1795), 4. “Angelo Santi Confectioner No. 81, King-street,” Charleston Oracle (January 5, 1807), 4. “The Subscriber,” Charleston Strength of the People (January 13, 1810). South Carolina Marriage Index, 1600-1820. Mortuary notice Francoise Judet Litant Angelo Santi, Savannah Republican (June 13, 1811), 3.