Taverns, Long Rooms, Coffee Houses: 1783 to 1793

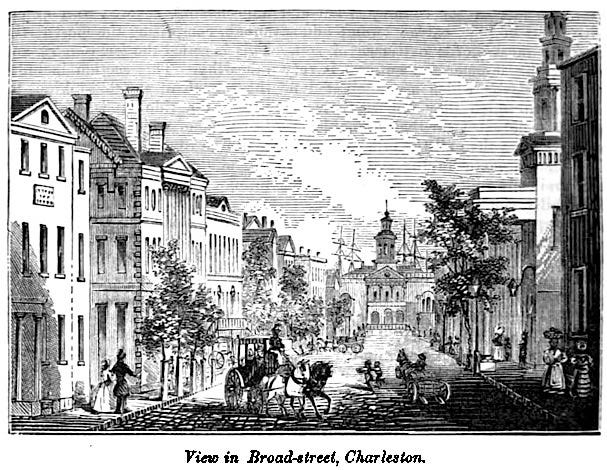

In the period after the American Revolution the port cities of the new United States vied to reestablish the institutions of hospitality—the inns, taverns, coffeehouses, and confectioner’s shops that would appear inviting to merchants and genteel visitors from around the Atlantic world. Charleston sought to reclaim its reputation as a center of deluxe entertainment in 1783 to 1788, despite the lack of a stable currency, governmental disinclination to prosecute debtors, and interruptions in the flow of wine, olive oil, and other fixtures of fine dining caused by British disruptions of American oceanic trade. A handful of major public houses opened at key locations in the city—but the difficulties of business would drive proprietors into bankruptcy, so we have four major houses run by several regimes during the early republic. It is best perhaps to identify them by location:

92 Broad Street

City Tavern

William Thompson 1783-1784

James Milligan 1784-1788

Peter Contaretti 1788-1788

Turner’s Long Room

Capt. Thomas Turner 1789-1803

4 Broad Street (or) 51 East Bay Street

Exchange Coffeehouse

Sampson Clark 1784-1785

Augustine Moore 1785-1787

Captain William Robeson 1787-1796?

63 East Bay

McCradys Tavern

Edward McCrady 1783-1792

Harris’s Long-Room or Harris’s Hotel

John Hartley Harris 1792-1794

Globe Tavern or Coates’s Coffee House

Catharine Coates 1794-1799

Jessop’s Hotel

Jeremiah Jessop 1799-1803

20 Tradd Street

Carolina Coffee House & Tavern

John Williams 1787-1809

Around these major institutions there was a constellation of lesser public spaces in which alcohol was served, visitors fed, and food retailed or served. In 1783 ninety three premises were licensed to sell alcohol—these included groceries, dram shops, boarding houses, brew houses, and taverns. Thirty-four of these licensees were women.

The four major houses bore a variety of names—coffeehouse—tavern—long room—hotel. The truth of the matter was that they were all composite institutions, combining functions of traditional British institutions to suit a new situation of public socializing, drinking, and dining. The coffeehouse, originally a Puritan institution inaugurated during Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth, offered caffeine (coffee, tea, and perhaps chocolate) and spaces arrayed for business—semi-private booths, meeting rooms, newspapers from around the Atlantic, a refectory table for dining, and at least one large space in which to hold auctions. It was overwhelmingly a masculine space. The tavern was more heterosocial, though single women did not venture alone into a tavern at risk of her reputation. It served alcohol—cider, perry, beer, wine (if a better class establishment), and sometimes spirits. It was a place of resort for amusement, business, or ingestion. Tavern food varied greatly in terms of quality and the bill of fare minimized choice. Variety applied to the beverages not the dinner offerings. The hotel emerged as a novelty in the English speaking world in the 1790s—at about the same time the restaurant became an institution. It subsumed the old task of lodging that inns had traditionally served, offered deluxe dining, public rooms, and saloons. Hotels were distinguished by the scale of their accommodations as well. Long rooms were an importation of ball rooms from aristocratic houses or civic palaces into the space of the coffee house or tavern. Long rooms were multi-purpose spaces that could be adapted to concerts, assemblies, auctions, or mass meetings.

Every ambitious would-be public host wished to accommodate the men of commerce who would flood the city after peace had been established. So they offered the amenities of a coffee house; yet they also sought the merry conviviality of a tavern, so installed a bar amid the coffee urns. The first to attempt this marriage was Mrs Ramadge who opened a Coffee House on the corner of Broad and Church Streets in Spring of 1783. Since foreign merchants would need lodging and boarding, they were offered as well.

Pennsylvanian William Thompson opened Charles-Town Tavern (popularly called City Tavern) a month after Mrs. Ramadge, but could not spare rooms for lodgers. He compensated by emphasizing the variety and quality of his liquors and meals. Yet his Tavern incorporated a “Coffee-room, for the benefit of Merchants and other persons, together with the Newspapers of the day, as in the best kept Coffee-Houses of this Continent” (“To the Public,” South Carolina Weekly Gazette, June 28, 1783, 1). He had a long room and almost immediately began renting it for assemblies and club gatherings.

If Mrs. Ramadge and Mr. Thompson banked on their liquors to attract custom, Sampson Clark of the Exchange Coffee House on the corner of Broad Street and East Bay, across from the Charleston Exchange, advertised the quality of his food. He secured a London cook named Jones and promised “dinners, suppers, &c. when bespoke, on the shortest notice, and elegantly dressed, in the English and French taste” (“Exchange Coffee House and Grape Tavern, South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, August 17, 1784, 2). In the notices of Clark and his successor as proprietor of the Exchange Tavern, pastry chef Augustine Moore, the shape of fine dining in post-Revolutionary Charleston was defined. Chocolate, tea and coffee was available from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. Customers could secure soups at 11: a.m.

South-Carolina Weekly Gazette and General Advertiser, September 22, 1784, 3.

The Exchange Coffee house featured Green Turtle Soup every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday—a dish that would come to define quality dining from Boston to Savannah in the 1790s. The Green Turtles, enormous oceanic creatures, were caught in the Caribbean and transported live to the ports of North America. Later they would be processed on factory ships and meat shipped world wide. Mock Turtle Soup and Oyster Soup were other regular offerings.

In July 1785 a formidable rival to Mr. Jones appeared in the city. Pastry cook and confectioner Augustine Moore set up shop at 20 Meeting Street. He too offered the soups, the dinners, the steaks, and the relishes. But he offered more: Portugal, seed, and iced cakes, custards and jellies, and pastries of every sort. In December of 1785 he took over the Exchange Coffee House from Sampson Clark and Mr. Jones (“Moore, Cook,” Charleston Evening Gazette, December 20, 1785, 4). Announcing his acquisition of the lease under the title “Moore, Cook,” he asserted the primacy of the culinary in Charleston hospitality. After 1785 a public host or hostess neglected food at his or her peril.

So what constituted noteworthy dishes in this first age of South Carolina’s fine dining? In addition to beef steak—the signature dish of Great Britain—Moore advertised ham and veal as every day offerings at the Exchange Coffeehouse (“Ham & Veal,” Charleston Morning Post, July 7, 1787, 4). During William Robeson’s proprietorship of the Exchange the list of main dishes was expanded, including “Oysters, dressed in every desirable manner, and all kinds of Poultry, roasted and boiled, hot and cold; with Relishes, to be had all hours in the day” (“Exchange Coffee-house,” Columbian Herald, December 17, 1795, 4). What were the desirable manners of serving oysters? Raw on the shell, stewed, roasted, and pickled. As early as 1785, Charleston had one eating house, specializing in oyster suppers and pickled oysters, Mrs. Fishers on Unity Alley (“All Kinds of Sweet Meats,” Charleston Evening Gazette, November 11, 1785, 3). Advertisements for other venues in the 1780s and 1790s named turkeys, ducks, chickens, and guinea fowls as fowl. While fish and game were central to the country hospitality of the plantocracy, the first venue to regularly offer both was Jeremiah Jessop’s The Charleston Recess and Bellevue Coffee House, three miles up Charleston neck, in 1803 (City Gazette, February 25, 1803, 1). Jessop, when he was located at 63 East Bay, in the late 1790s, had the most efficient public ice house in the city and introduced ice cream to the Lowcountry.