ISSUE 65, COLONIAL COOKING, Part 1: Culinary Antiquarianism

American Cookbooks & Culinary Antiquarianism

Before there was culinary history there was culinary antiquarianism. Culinary antiquarianism highlighted the charm of the old, valued suggestiveness over precision, gestured at a traditional civility and hospitality, connected foods with a way of life that is lost, or perishing, or imperiled, or at odds with present methods and manners. Its values stood at odds with scientific household management, nutrition, physical culture, and consumption ideologies such as vegetarianism, Grahamism, Hydropathy, or raw food consumption.

While the American centennial of 1876 ignited a national relic consciousness focused on the British American colonial era, the American Revolution, and the lives of the founders, with curiosity shops selling American antiques as well as oddments from Europe, there was no similar effort to capture and collect the foods and recipes of early America. No food vendor at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia sold old time dishes. Indeed the signal developments in the presentation of American food at the exposition was the restaurant devoted to southern cookery (the South being understood as an integral region) and a restaurant devoted to Jewish cuisine. The best-selling Centennial Cookbook by Mrs Ella E. Myers treated “Modern Cookery in All its Arts”.

Culinary antiquarianism emerged in print during the first decade of the twentieth century. Its inaugural books—Celestine Eustis’s Cooking in Old Creole Days (1903), Mrs Frederick Sidney Giger’s Colonial Receipt Book (1907), Maude A. Bomberger’s Colonial Recipes from Old Virginia and Maryland Manors (1907), Jacqueline Harrison Smith’s Famous Old Receipts (1908)—shared numbers of features: they collected recipes from women of high social standing whose names, or initials, and often place of residence were identified with the contribution, they highlighted recipes drawn from historical figures or associated with historic houses, they construed the word “colonial” loosely, meaning any time prior to Civil War, they interjected stories, verses, historical anecdotes among the recipes, and they represented the task of culinary memorialization in the volumes as a sororal exercise analogous to the 19th-century preservation initiatives taken by women in Philadelphia, Mount Vernon, Williamsburg, and New Orleans. Often there was the suggestion of a rapprochement between North and South enacted by elite women, in their common reverence for the culture of a time before the sectional strife of the mid-19th century.

The Society of Colonial Dames was founded in 1891 with the intention of employing genealogy as a grounds of cultural identity. Female descendants of approximately 9,000 registered Euro-American ancestors could seek membership in a national organition devoted to patriotism, preservation, and cultural memory. Networks such as this brought elite women from one region in contact with those of another.

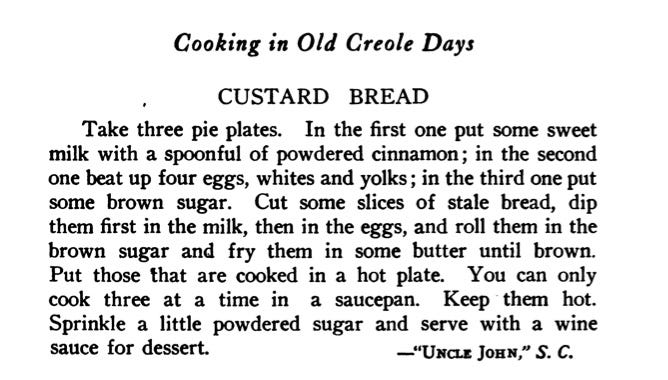

Regardless of this upper class women’s solidarity, there were particular regional concerns that were addressed in the books. Those of southern origin deployed a myth that the disappearance of the black cook in the wake of the Civil War led to a degeneration of cuisine that must be remedied. In Eustis’s introduction to Cooking in Old Creole Days, she concurred with a southerner’s observation that a deplorable consequence of Appomattox was “the disappearance of the colored cook”. She remembers “the marvelous skill of the Southern Cooks” that seemingly evaporated with the liberation of the slaves. Yet strangely for a vanished cohort, they figure rather frequently in the text of her collection, with recipes of contemporary black cooks such as South Carolinian “Uncle John,” Katie Seabrook, President McKinley’s chef, Celeste Smith, and Aunt Rachel Coffen figuring frequently in the pages.

There was no such attention to black cooks and their contributions to cookery in the works compiled in Philadelphia by Giger and Smith. Bomberg’s book on recipes from Maryland and Virginia is interesting in that certain recipes are attributed to places—historic houses—and others from certain female residents of those houses. Should we presume that those that the historic houses generated were actually contrived by black cooks in those two former slave states? Some of these recipes are remarkable such as the Mint Brandy of Hampton.