Potato Bread

Somebody somewhere in the United States is trying to make bread cheaper—this is true of every age and most every place since the republic began. Wheat is often costly. It was singularly subject to diseases and pests over the years. So the usual recourse was to add some other starchy “farinaceous” substance—rice or rice flour, nut meal, bean meal, or potatoes to the dough—up to ¼ of the mass—to form a less costly loaf. Because this additive did not contain gluten, it would not rise with yeast if the percentage of material exceed ¼ of the total. The invention and popularization of chemical leavens in the nineteenth century provided a work around. If you were making biscuits or light breads you could up the percentage of rice or potato and still get a rise in the oven.

Patriot-printer Isaiah Thomas of Massachusetts provided the public with the first recipe for potato bread in his 1782 Thomas’s Almanack. In 1791 the Philadelphia Independent Gazateer republished in translation the instructions of French Agronomist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier for making “Potato Bread without the Admixture of Flour.” His method-adding yeast and water to a 50-50% mixture of potato starch and mashed potatoes, letting it rise, forming it into small loaves and then baking it for 2 hours at a moderate heat. No—the result doesn’t have the crumb or lightness of wheat bread, but it is edible. (Parmentier is the great culinary theoretician of the role of potato starch in European cookery. He wanted to make the potato a French staple crop, but the peasantry would not listen to his lectures about nutrition and economy. Indeed he couldn’t get them to grow the plant,\ until he prohibited its possession by the lower classes and placed and armed guard around the royal garden plot of potatoes. The plants were all instantly stolen and propagated through the country.)

One can gauge the popularity of a baked good by its appearance in a commercial bakery or confectionary. It is advertised in 1807 by Martha Maubry, a baker located at 206 King Street, Charleston, SC: “Hot Bath Buns and Muffins , every morning and Rusks Whigs, and Potato Bread in the afternoon” [Charleston City Gazette (September 25, 1807), 2.

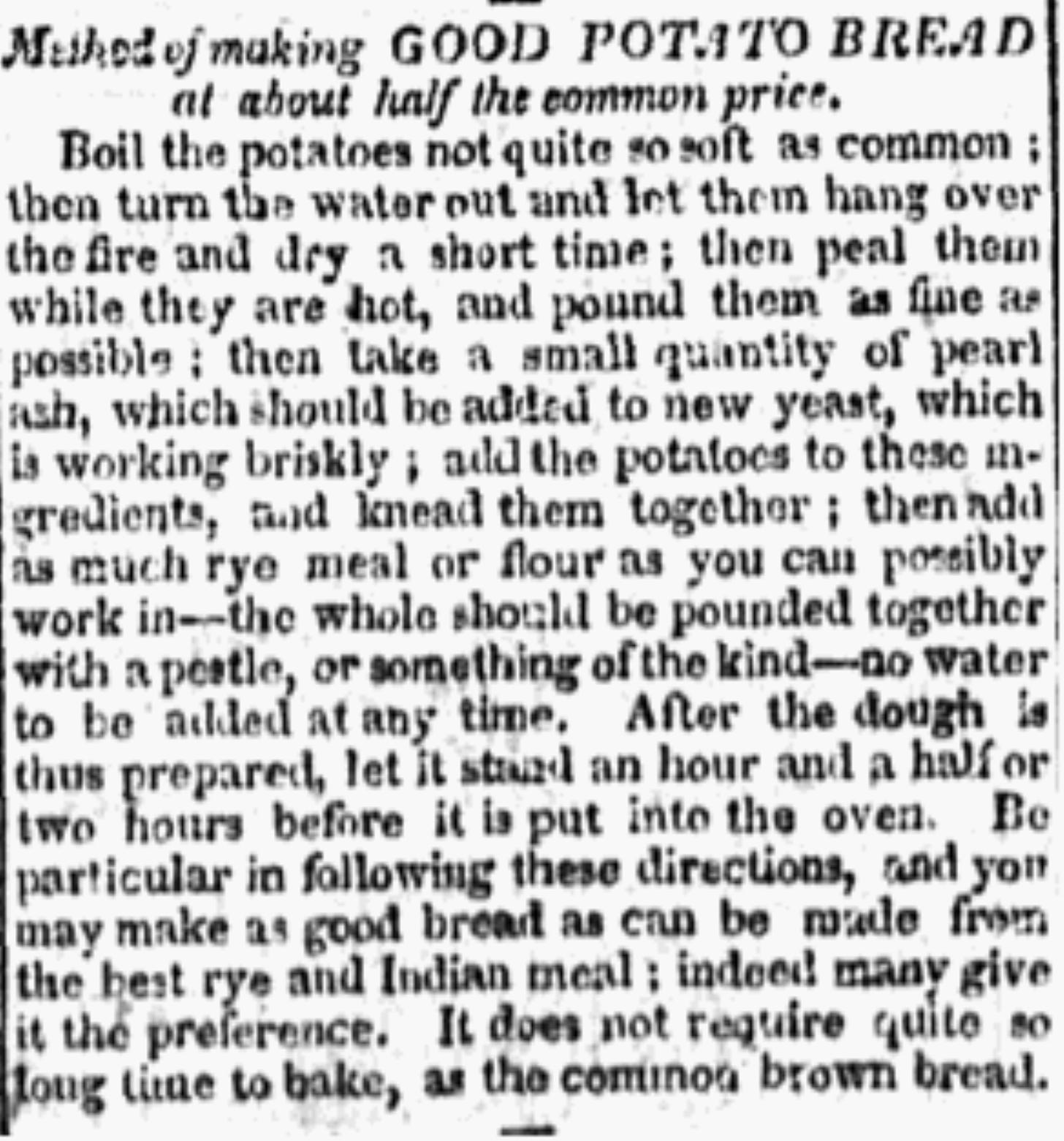

In the early American recipes that call for a mixture of potato mash and glutinous flour, pearl ash is added to yeast, and then worked briskly into a potato & grain flour mixture. Rye is the most often named grain whose flour works well with potato mash.

What is never mentioned in these early recipes is the variability of texture in potato varieties. Waxy potatoes are not the kind favored for baking; rather the starchy, floury kind. [New York Evening Post (December 2, 1816), 2.] Of currently available 19th century important heirloom tomato varieties: yes to the Early Rose, no to the Mercer. One thing that is always mentioned, however, is “at about half the common price.”

Every time that the price of flour became exorbitant, newspaper editors would print a commendation of potato bread, touting its cheapness. As the Boston Traveler argued on January 20, 1838, “hard times are productive of expedients. That of making potato bread would never have been thought of, when flour was less than ten dollars per barrel. It has been used, however, with great success in some parts of the country, and were hereby request all good housewives to make trial of it” [Boston Traveler (January 20, 1837), 2.] Whenever financial panics, wars, or grain crop failures occurred, an up-tick in the interest in potato bread occurred. Yet at the end of the nineteenth century it could be said that only one section of the populace had truly embraced it—the Germans—who made kartoffelbrot a fixture at German bakeries in America’s cities.

Strangely the closest that the general public came to adopting potato bread was during the greatest moment of anti-German sentiment ever to trouble America: the later 1910s when World War One propaganda anathematized all things German. Then the U. S. government determined that the widespread consumption of Potato Bread would de-stress grain supplies, and improve home economy among the citizenry. USDA articles and lectures flooded the magazines and gazettes. “Potato Bread is New Economy Fad” (1915), “U. S. Gov’t Urges Use of Mixed Flour“ (1915), “Uncle Sam has this about Potato Bread” (1916), “Potato Bread Economical” (1918), “Potato Bread Equal to Wheat” (1918), “Liberty Bread to be demonstrated at State Fair” (1917), “Potato Victory Bread” (1918). Rebranding potato bread as Liberty Bread or Victory Bread in the end did not provoke a mass conversion of Americans to potato based breads. For the century since the end of World War I it has remained a specialty item, despite the perfection of some excellent recipes for the bread.

When Rococo German Bakery in Charleston was open, in those golden days before COVID tainted our social life, they regularly offered a classic Potato Bread that made some of the best toasted I’ve ever tasted. One bite tolde me that Kartoffelbrot was no “economy loaf” but a noble member of the family of the staff of life.